In 2003, as part of the national “Amber Alert” statute, former President George W. Bush signed “Suzanne’s Law” which is also known as “Jennifer Act” mandating authorities to alert the National Crime Information Center (NCIC) whenever someone between the ages of 18 and 21 is reported missing. Police were previously only compelled to report missing people who were under the age of 18.

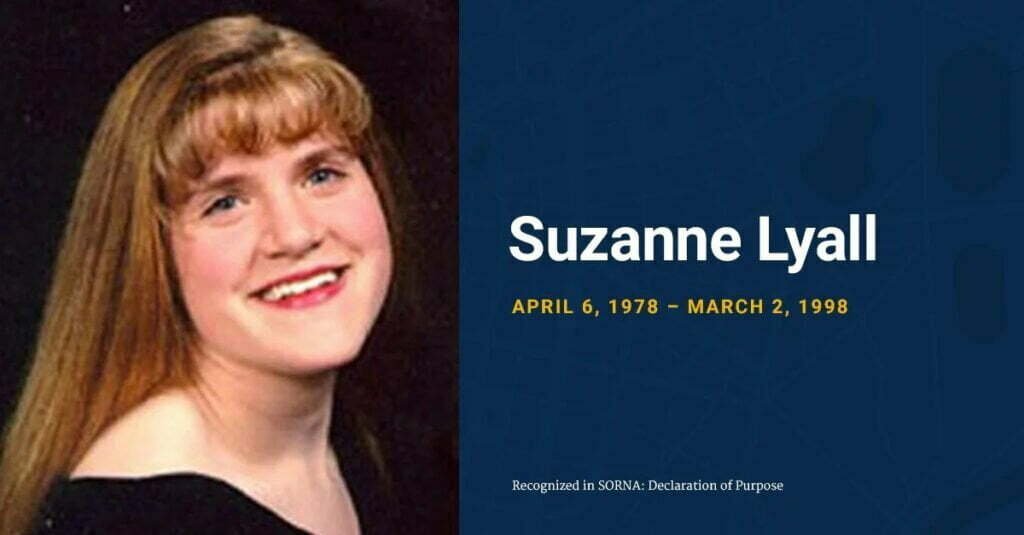

The statute bears Suzanne Lyall’s name; she was a 19-year-old student at the University of New York in Albany who vanished or went missing in 1998. The provision is meant to encourage police to launch quick investigations into missing young people.

Many law enforcement organizations are still uninformed of the law change and their expanded duties. The law enforcement agency can also report the information to NCIC and obtain services like age enhancement technology and poster production from the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. Additionally, police are now permitted to add long-term missing people up to the age of 21 who were reported missing prior to the law’s implementation.

In honor of Suzanne Lyall, a student at the State University of New York in Albany who has been missing since 1998, a federal legislation bears her name.

The Suzanne Lyall Campus Safety Act

Former President Bush signed a measure in August 2008 requiring institutions to establish rules describing the function of each law enforcement agency — campus, municipal, and state — in a violent crime investigation on campus.

The Suzanne Lyall Campus Safety Act is the name of the law, which is an addendum to the wider Higher Education Opportunity Act. During a preliminary inquiry, it is intended to reduce snags and misunderstanding. On the state level, a corresponding law was passed in 1999. The Campus Safety Act of New York, which was partly influenced by Lyall’s disappearance, mandates that all state-funded universities “have formal plans that provide for the investigation of missing students and violent felony offenses committed on campus.”

Amber Alert

The National Crime Information Center (NCIC) of the Federal Bureau of Investigation received 337,195 complaints of missing people involving kids in 2021. As of December 31, 2021, 93,718 records from a total of 521,705 missing person reports reported to NCIC were still active. 32 percent of the current missing people listings were for children.

In cooperation with OJJDP, NCMEC aids law enforcement in investigations involving missing children by providing crucial intervention and preventative services to families.

Authorities can send out notifications on various platforms and in various jurisdictions when a youngster goes missing. All 50 states, the District of Columbia, Indian country, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and 31 other countries now use the AMBER Alert system thanks to assistance from OJJDP.

As of January 2, 2023, 131 children have been saved as a result of wireless emergency warnings, and 1,127 children had been safely recovered through the AMBER Alert system. In the entire country, there are 82 AMBER Alert plans.

To support the AMBER Alert program, OJJDP works with various partners from the nonprofit, commercial, and technological sectors, including NCMEC, federal law enforcement organizations, cellphone carriers, Internet service providers, social media platforms, and the Outdoor Advertising Association of America.

Investigation of Missing Persons

The Crime Control Act of 1990 is amended by “Suzanne’s Law” so that there is no waiting period before a law enforcement agency launches an investigation into a missing person under the age of twenty-one (21) (to include children of residents) and reports the missing person to the National Crime Information Center of the Department of Justice.

Suzanne Lyall, a student at the State University of New York in Albany who has been missing since 1998, is honored by having “Suzanne’s Law” established in her honor. Police were previously only required to notify missing people who were under the age of eighteen. On April 30, 2003, former President Bush signed a legislation requiring police to launch an immediate inquiry into cases of missing children.

This law was a component of the national Amber Alert bill. An act requiring universities to establish procedures describing the responsibilities of each law enforcement agency — campus, municipal, and state — in investigating a violent crime on campus was signed into law by the former president Bush in August 2008.

Suzanne’s Law and Legal Definition

President Bush enacted Suzanne’s Laws, a federal statute pertaining to missing individuals, as part of the global “Amber Alert”. It stipulates that there should be no delay before a law enforcement agency launches an inquiry into a missing person under the age of 21 and notifies the Department of Justice’s National Crime Information Center of the missing person’s whereabouts. It alters Section 3701 (a) of the Crime Control Act of 1990 to do this.

If a person between the ages of 18 and 21 goes missing, local authorities are required to immediately notify the National Crime Information Center. The law is known as Suzanne’s Law in honor of State University of New York at Albany student Suzanne Lyall, who has been missing since 1998.

The Crime Control Act of 1990 is amended by Suzanne’s Law, which mandates that each State reporting under the Act’s provisions regarding missing children make sure that no law enforcement organization within the State establishes or maintains any guidelines requiring the observance of a waiting period before accepting a report of a missing child.

Defines a “missing youth” as a person between the ages of 18 and 21 whose whereabouts are unknown, who has a physical or mental disability, who might be with someone else when their physical safety is in danger, or whose disappearance is surrounded by signs that suggest it might have been an unintentional disappearance.

Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention

To prevent and address adolescent victimization and delinquency, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) offers national leadership, coordination, and resources. The Office supports the development of efficient and fair juvenile justice systems that make communities safer and enable children to lead fulfilling lives.

Efforts

OJJDP provided more than $50 million in fiscal year (FY) 2022 to help find missing children, stop kidnapping, and offer technical support and training.

For more than 30 years, OJJDP has collaborated with the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC). In order to improve law enforcement’s efforts to find missing and exploited children, OJJDP granted the Center more than $38.7 million in FY 22. This money will go toward training and technical support.

Fox Valley Technical College received a $4.4 million grant from OJJDP as part of the National AMBER Alert Training and Technical Assistance Program in FY 22 to help train first responders and law enforcement to better handle AMBER Alert activations.

Crime Control Act of 1990

A federal statute of the United States outlaws the trade in fake goods and services under Section 3701(a) of the Crime Control Act of 1990. Trafficking or attempting to traffic in products or services that are fraudulently branded or recognized as real goods or services is against the law.

Trafficking, according to the law, is defined as “transporting, transferring, or otherwise disposing of, to another person for purposes of commercial advantage or private financial gain, or knowingly receiving, in connection with a transaction affecting interstate commerce, goods or services that: (1) bear a counterfeit mark; (2) have been falsely labeled or identified; or (3) are intended to be used in committing a criminal offense.”

If this legislation is broken, there may be legal repercussions, such as fines and jail time. The severity of the punishment is determined by the cost of the fake products or services used in the trafficking violation. The legislation also specifies civil fines and remedies, such as restraining orders and the confiscation of assets related to the violation, in addition to the criminal sanctions.

This law’s goal is to prevent the selling of fake products and services, which may be detrimental to both customers and the economy. Products that are counterfeit may be of lower quality and put customers’ safety at risk. The selling of fake goods may also hurt genuine companies and lower tax and duty income for the government.

Purpose of Suzanne’s Law or Jennifer Act

The law’s goal is to enhance cooperation and communication among law enforcement authorities when it comes to situations of missing people, especially young adults between the ages of 18 and 26 who are not considered minors or adults. The National Crime Information Center (NCIC) database must be updated as soon as possible with details on a missing individual, including an image and any pertinent identifying information, according to the law. Law enforcement organizations must also make a reasonable attempt to collect DNA samples from the families of missing people and submit that data into the FBI’s CODIS (Combined DNA Index System).

The law funds training programs for law enforcement personnel and gives missing person’s families access to resources like a national information hub for missing people and a national communication network to help with missing person searches. The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children must be notified by law enforcement authorities as soon as possible after receiving a complaint of a missing kid, according to the law.

The overall goal of Suzanne’s Law of Missing Persons is to enhance the response to missing person situations, particularly those involving young adults who might not receive the same degree of attention and resources as missing children or adults. The goal of the law is to enhance cooperation and communication between law enforcement agencies and to give families and officers access to resources that will help in the search for missing individuals.

Conclusion

The Jennifer Act, also referred to as Suzanne’s Law of Missing Persons, is a significant federal law that seeks to enhance cooperation and communication between law enforcement agencies in cases of missing persons, especially young adults between the ages of 18 and 26 who are not categorized as juveniles or adults. The law established a nationwide clearinghouse for missing person information, funds training programs for law enforcement personnel, and mandates that law enforcement organizations record data on missing people into national databases.

The Jennifer Act is a significant step in improving the handling of situations involving missing persons and giving families and law enforcement personnel the tools they need to assist in the search for those who have vanished. The law aims to enhance the cooperation and communication required to return these young adults home safely while also acknowledging the special difficulties experienced by families and law enforcement authorities in situations involving missing young adults.

FAQ’s: About Suzanne’s law

What is the Suzanne’s law in California?

Suzanne’s Law is a California law that requires law enforcement agencies to immediately notify the National Crime Information Centre (NCIC) when a person between the ages of 18 and 21 is reported missing. The law was named after Suzanne Lyall, a student at the State University of New York at Albany who has been missing since 1998.

What happened to Suzanne Lyall?

Suzanne Lyall was a college student who went missing on March 2, 1998, in Albany, New York. She was last seen at the Crossgates Mall bus stop, where she was scheduled to board a bus to return to her college campus. Unfortunately, Suzanne’s whereabouts remain unknown and her case is classified as a missing person case. Despite an extensive investigation and ongoing efforts, her disappearance remains unsolved.